by Anne Walther | LIFESTYLE

In a few words, one could say that wabi sabi is the beauty of imperfect things. Of course, that would be overly simplistic explanation for such a deep and profoundly rooted notion in the Japanese spirit. Something between an artistic concept, a philosophy of life and a personal feeling, wabi sabi is everywhere in Japanese culture.

1. What is Wabi Sabi?

© Wabisabimind, Garden Entrance

In Japan, wabi sabi is imperceptible but everywhere: a crack on a teapot, the wood of an old door, green moss on a rock, a misty landscape, a distorted cup or the reflection of the moon on a pond.

In Wabi Sabi: The Japanese Art of Impermanence, Andrew Juniper defines wabi sabi as "an intuitive appreciation of ephemeral beauty in the physical world that reflects the irreversible flow of life in the spiritual world.”

Related to landscapes, objects and even human beings, the idea of wabi sabi can be understood as an appreciation of a beauty that is doomed to disappear, or even a ephemeral contemplation of something that becomes more beautiful as it ages, fades, and consequently acquires a new charm.

© Didier Moïse / Creative Commons, Ryoanji Temple Garden

The term wabi sabi is composed of two kanji characters. The second part, sabi (寂) is said to date back to the eighth century, when it was used to designate desolation in a poetic way. From the twelfth century, the term evolved and referred more precisely to the delightful contemplation of what is old and worn. It was also used to talk about the beauty of faded or withered things. Sabi could also mean “old and elegant”, or “being rusty”, with an untranslatable impression of peacefulness.

© Olivier Bruchez / Creative Commons, Nezu Museum Garden

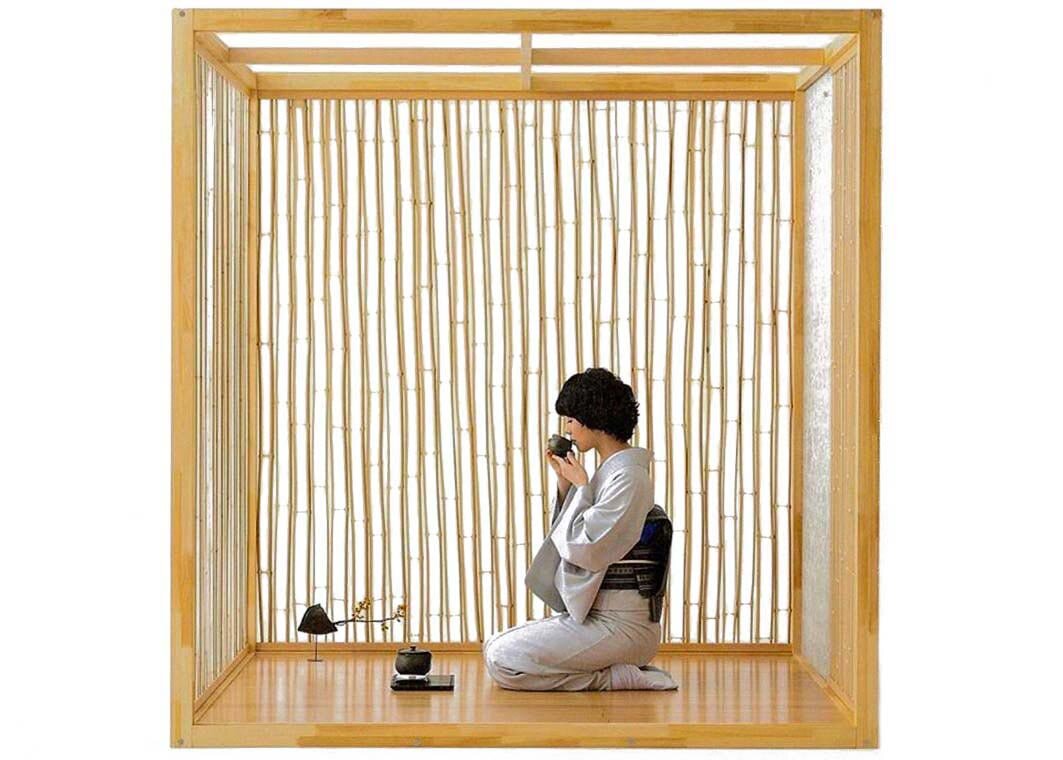

The term wabi (侘) only appeared in the fifteenth century to designate a new aesthetic sensibility closely related to the tea ceremony, which referred to the general atmosphere and to the objects used during this formal service. The definition of wabi can be traced back to loneliness or melancholy, to the appreciation of a serene life, far from the urban hustle and bustle.

© Yufuku, Mindscape by Ken Mihara

The term wabi sabi (侘寂) remains difficult to translate. For Japanese people, wabi sabi is a feeling, more than a concept, that can be found in classical Japanese aesthetics: flower arrangement, literature, philosophy, poetry, tea ceremony, Zen gardens, etc. Wabi sabi goes against contemporary over-consumption, but also encourages simplicity and authenticity in everything.

2. Where Does Wabi Sabi Come From?

This notion of wabi sabi is a feeling that has certainly always been part of Japanese sensibility. Its origin can be found in the story of Sen no Rikyu, the sixteenth century Zen monk who theorised the tea ceremony as it is still practiced in contemporary Japan.

According to the legend, the young Rikyu, eager to learn the codes of the ancestral ritual of tea ceremony, went to find a recognized tea master named Takeeno Joo. The latter wanted to test the abilities of his new apprentice and asked him to take care of the garden. Rikyu cleaned it from top to bottom and raked it until it was perfect. However, before presenting his work to his master, he shook a cherry tree and sakura flowers fell on the ground. This touch of imperfection brought beauty to the scene and that is how the concept of wabi sabi was born.

Black Raku Matcha Bowl, available at Japan Objects Store

Sen no Rikyu is still considered as one of the greatest and most influential tea masters in history. He helped to transform the tea ceremony as it was previously practiced, with luxury utensils and exuberance, into a refined ritual. From the simplicity of the objects and the minimalistic atmosphere of the tearoom emanated a delicate beauty that could not be equaled.

By using imperfect objects, sometimes broken and repaired, in a room devoid of superfluous items, Rikyu made the moment of tea tasting a true communion for the spirit, which was nourished by the following principles: harmony, purity, respect and tranquility. This kind of ceremony is also referred to as wabi-cha (cha being the Japanese word for tea).

Goma Bizen Ware Yunomi Teacup Set by Hozan, available at Japan Objects Store

Nowadays, the most prestigious tea ceremonies are still carried out with teacups that are several hundred years old and antique utensils. In Japanese pottery, cups are often distorted and irregular because each object must be unique to have its own charm. The imperfect beauty of wabi sabi is found in many other Japanese art forms. To find out more about wabi sabi in the ceramic arts, check out What is Bizen Ware? 7 Things to Know About Wabi-Sabi Pottery.

3. Wabi Sabi in Japanese Art

Monk Rensho Riding His Horse Backwards by Matsumura Goshun, around 1784

Wabi sabi is an artistic sensitivity as much as an ephemeral feeling of beauty. It celebrates the passage of time and its sublime damages. In many art forms in Japan, this notion of prettiness through imperfection is present. Check out Everything You Might Not Know About Japanese Art.

In literature, wabi sabi can be found in certain types of haiku, an ancestral art imbued with Zen philosophy. Traditional haiku consist of three sentences that comprise a kireji (cutting word), 17 phonetic units in a 5-7-5 pattern, and a kigo (seasonal reference). This form of codified poetry allows to express the instantaneous beauty of a scene and is therefore appropriate to express the feeling of wabi sabi.

© Adrian Freedman, Shakuhachi Flute

The shakuhachi, a traditional Japanese flute, also embodies the ideals of wabi sabi. It boasts a simple structure: a rough bamboo pipe, open at both ends, with five holes and a bottom end made from the root end of the bamboo stalk. Even if it seems unsophisticated, a shakuhachi is nevertheless a work of art, craftsmanship and engineering. Honkyoku (original pieces) flute music played by Japanese Zen monks is also considered wabi sabi.

© Tetsuya Miura, Ikebana by Nishiyama Hayato

Since they live on a land that is subject to the vagaries of earthquakes and tsunamis, the relationship that Japanese people have with nature is exceptional. Consequently, it is not surprising that they respect nature as much as they fear it. This admiration finds a form of representation in ikebana, which encourages natural magnificence in simplicity.

Since wabi sabi defines beauty in its ephemeral nature, a single flower in a vase perfectly embodies this concept. Based on harmony between asymmetry, depth, and space, ikebana brings out the beauty of a pure floral composition. Here you can find out All You Need to Know About Ikebana.

Bonsai, the famous Japanese miniature trees, often feature textured wood, fragments of deadwood, and plants with hollow trunks, all aimed to emphasize the passing of time and the beauty of nature.

© Tedmoseby / Creative Commons, Ryoanji Garden

As mentioned above, the tea master Sen no Rikyu was able to express a feeling of wabi sabi by arranging a Zen garden. What could be more evocative than a garden, where the ephemeral elements (green mosses, growing shrubs, fresh flower petals) and the immutable components (raked sand, old stones) are harmoniously mixed. Japanese gardens and their evolution over time and throughout the seasons are countless illustrations of wabi sabi. If you’re interested, check out these 5 Types of Authentic Japanese Garden Design You Should Know to find out more.

4. Kintsugi: The Art of Beautiful Repairs

Tea Bowl with Gold Lacquer Repairs, in the Style of Koetsu, Unknown Raku Ware Workshop, Attributed to Tamamizu Ichigen, 18th Century, Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian

Kintsugi is an old Japanese technique for repairing objects, which consists of mending the areas of breakage with lacquer mixed, or dusted, with gold powder. Instead of throwing away broken or damaged ceramics, this art gives a second chance to bowls, cups, or vases, which are embellished by this meticulous work. This focus on reuse and repair is related to the concept of mottainai, or the avoidance of waste, which is of greater importance today than ever.

Tea Bowl with Gold Lacquer Repairs, White Satsuma Ware, 17th Century, Freer Collection of Art, Smithsonian

Behind this practice, intricately linked to the notion of wabi sabi, lies a wish to celebrate the beauty of time passing. Kintsugi is also used as a metaphor of resilience by health professionals. One may experience trauma, be damaged and then be reborn, more beautiful, and stronger.

5. Wabi Sabi in Daily Life

Wabi Sabi For Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers by Leonard Koren

Leonard Koren is an American architect who theorised wabi sabi aesthetics and helped spread this perception outside of Japan. In his book Wabi Sabi For Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers (1994), he made a distinction between the form and spirit of wabi sabi.

The form is the material manifestation of the notion, through objects and their arrangement, or through sensations or sounds. The spirit is the philosophical way to apprehend wabi sabi and thus to experience it. In Koren’s opinion, wabi sabi happens, it cannot be created. In an interesting demonstration, he compares the feeling of wabi sabi to a person who would fall in love with another person who is considered unattractive. The first person would perceive and appreciate the imperfect beauty of the second.

Wabi Sabi Further Thoughts by Leonard Koren

In recent years wabi sabi has been gaining recognition in the Western world and there are numerous books covering the subject. More than twenty years after his first publication, Leonard Koren wrote a second book, Wabi Sabi Further Thoughts.

Wabi Sabi: The Japanese Art of Impermanence by Andrew Juniper

Wabi Sabi: The Japanese Art of Impermanence, by Andrew Juniper, is also considered as a reference book on the subject. Our last recommendation, Wabi Sabi Japanese Wisdom for a Perfectly Imperfect Life, by Beth Kempton, was highly appreciated by Amazon readers.

Wabi Sabi Japanese Wisdom for a Perfectly Imperfect Life by Beth Kempton

As a sensitivity that can therefore lead to happiness, or to an acceptance of the beauty of simple and natural things, wabi sabi philosophy is applicable every day. It is a daily way to experience little joys. When admiring a landscape, an object, or a painting, during a conversation with friends or when sharing a moment with a good company, everyone can feel the notion of wabi sabi.

Elusive and beautiful, wabi sabi is an integral part of Japanese life. Omnipresent, it is the basis of the delicate Japanese sensitivity that so often surprises us. Today, this notion deserves to be given more emphasis since it encourages a return to humble and unpretentious values.

January 8, 2021 | Lifestyle

Source: Japan Objects